| Image title |

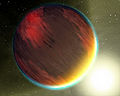

This artist's concept shows a cloudy Jupiter-like planet that orbits very close to its fiery hot star. NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope was recently used to capture spectra, or molecular fingerprints, of two "hot Jupiter" worlds like the one depicted here. This is the first time a spectrum has ever been obtained for an exoplanet, or a planet beyond our solar system.

The ground-breaking observations were made with Spitzer's spectrograph, which pries apart infrared light into its basic wavelengths, revealing the "fingerprints" of molecules imprinted inside. Spitzer studied two planets, HD 209458b and HD 189733b, both of which were found, surprisingly, to have no water in the tops of their atmospheres. The results suggest that the hot planets are socked in with dry, high clouds, which are obscuring water that lies underneath. In addition, HD209458b showed hints of silicates, suggesting that the high clouds on that planet contain very fine sand-like particles.

Capturing the spectra from the two hot-Jupiter planets was no easy feat. The planets cannot be distinguished from their stars and instead appear to telescopes as single blurs of light. One way to get around this is through what is known as the secondary eclipse technique. In this method, changes in the total light from a so-called transiting planet system are measured as a planet is eclipsed by its star, vanishing from our Earthly point of view. The dip in observed light can then be attributed to the planet alone.

This technique, first used by Spitzer in 2005 to directly detect the light from an exoplanet, currently only works at infrared wavelengths, where the differences in brightness between the planet and star are less, and the planet's light is easier to pick out. For example, if the experiment had been done in visible light, the star is so much brighter than the planet that the total light from the system would appear to be unchanged, even as the planet disappeared from view.

To capture spectra of the planets, Spitzer observed their secondary eclipses with its spectrograph. It took a spectrum of a star together with its planet, then, as the planet disappeared from view, a spectrum of just the star. By subtracting the spectrum of the star from the spectrum of the star and planet together, astronomers were able to determine the spectrum of the planet itself. |